For decades, the success of supply chain and logistics operations in the mining sector was measured by a straightforward and narrow set of metrics: cost per tonne, equipment uptime, and the unwavering reliability of material moving from the mine pit to the port. If the haul trucks were consistently rolling, the barges were sailing on schedule, and crucial exports cleared customs without delay, the entire system was deemed a success. This traditional definition, however, no longer holds in an industry now sitting at the complex intersection of intense environmental scrutiny, strict carbon accountability, rising community expectations, and mounting regulatory pressure. Sustainability has evolved from a peripheral conversation into a core operational constraint, as fundamental as fuel availability or infrastructure access once was. What distinguishes this current shift is its permanence; carbon reporting, emissions reduction, and environmental responsibility are not fleeting trends but deep structural changes that are set to govern how mining logistics are planned, funded, and managed for the next generation.

1. A New Era for Mining Supply Chains

The traditional metrics that once defined logistics success have become glaringly insufficient in the modern operational landscape. A singular focus on minimizing cost per tonne and maximizing the speed of material transport overlooked significant externalities that are now coming to the forefront of stakeholder concerns. This older model prioritized immediate economic efficiency, often at the expense of long-term environmental health and social license. The assumption was that as long as the core function of extraction and transportation was maintained, other impacts were secondary. This perspective allowed for the development of highly optimized but environmentally and socially brittle supply chains. These systems were engineered for a world where carbon was not priced, community consent was assumed, and regulatory frameworks were far less stringent. Today, that world no longer exists, and the very definition of an “efficient” supply chain is being fundamentally rewritten to include resilience, transparency, and sustainability as non-negotiable components of performance.

The pressures reshaping mining logistics are multifaceted and deeply embedded in global economic and social trends. Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) criteria are no longer simply a section in an annual report; they are a critical factor in securing capital, insurance, and long-term operating licenses. Investors and financial institutions increasingly screen projects based on their environmental footprint, demanding credible data on emissions and clear strategies for reduction. Simultaneously, local communities and regulatory bodies are holding companies to higher standards of accountability, expecting them to mitigate their impact on local ecosystems and contribute positively to regional development. This convergence of financial, social, and political pressure signifies a permanent realignment. The industry is moving from an era of compliance-driven adjustments to one where sustainability is integrated into the core design and strategy of logistics, shaping decisions from fleet procurement to route planning in a way that will define industry leaders for years to come.

2. Necessary Actions for Mining Companies

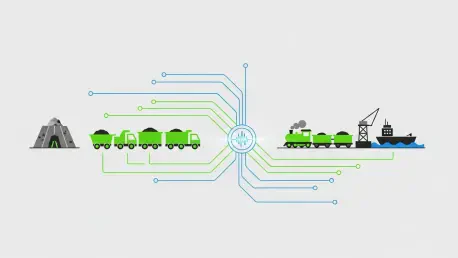

Mining companies and asset owners now face a critical decision: to treat sustainability as a mere reporting exercise to satisfy compliance or to deeply embed it into the fabric of how logistics decisions are conceived and executed. The first and most crucial step in this transformation is achieving comprehensive visibility. A significant number of mining supply chains still operate with a fragmented understanding of their end-to-end emissions, particularly beyond the immediate mine gate. Critical data related to third-party haulage, river and coastal transport, port congestion, and variations in fuel quality often reside in disparate systems or with various contractors, preventing a single, accountable view of the total carbon footprint. Without credible, consolidated data, any carbon reduction targets remain purely aspirational rather than actionable, making it impossible to identify key emission hotspots, measure the impact of interventions, or report progress to stakeholders with confidence. True operational change begins with a clear and honest accounting of the entire value chain’s impact.

Following the establishment of data visibility, the next imperative is to approach logistics through the lens of proactive design rather than reactive retrofitting. Companies must fundamentally reassess their material flows with emissions reduction as a primary objective. This involves a strategic evaluation of shorter transport routes where feasible, orchestrating modal shifts from carbon-intensive road transport to more efficient rail or water-based systems, and improving asset utilization to drastically reduce the number of empty runs. Furthermore, it requires a concerted effort to adopt cleaner fuels and invest in electrification where infrastructure permits. While these decisions may not always be cost-neutral in the immediate short term, they are increasingly pivotal in determining a company’s ability to secure financing and maintain its social and legal license to operate. Finally, clear and transparent communication of intent is essential. Stakeholders, from regulators to downstream buyers, are no longer satisfied with generic sustainability statements. They demand to see pilot projects, strategic partnerships, and an open discussion of the trade-offs involved.

3. The Government’s Role as a Supportive Partner

Local, regional, and national authorities hold a decisive role in determining whether mining supply chains can transition responsibly or become stalled by conflicting mandates and inadequate support. For a successful transformation, governments must act as enablers of change, not just as enforcers of regulations. A critical area for government intervention is the alignment of carbon policy with operational reality, particularly in remote regions where logistical alternatives are severely limited. Imposing stringent emissions standards without acknowledging the practical constraints of available infrastructure or technology can lead to operational disruptions rather than sustainable progress. Carbon taxation and environmental regulations are most effective when they are paired with practical, clearly defined pathways for compliance. When rules are predictable, consistently enforced, and developed with industry input, companies are far more willing and able to make the significant long-term capital investments required to innovate and decarbonize their supply chains ahead of compliance deadlines.

Beyond policy, governments can accelerate the transition by investing in shared, low-carbon infrastructure that benefits the entire industry. Public funding for upgrades to rail networks, inland waterways, and port efficiency can significantly lower the emissions footprint for all users, creating economies of scale that individual companies might struggle to achieve alone. Such investments de-risk the transition for operators and create a more competitive and sustainable national logistics ecosystem. Additionally, providing well-structured transitional incentives can be instrumental. These programs can allow companies the time and financial support needed to adopt cleaner technologies, such as electric fleets or alternative fuels, without jeopardizing employment or national output. This collaborative approach, which combines clear regulatory expectations with tangible support, fosters an environment where the industry can pursue both economic productivity and environmental responsibility, ensuring that the transition to a greener supply chain is both ambitious and achievable.

4. The Real Barriers to Progress

While advanced technology often dominates discussions about modernizing logistics, the most significant obstacles in the mining sector are frequently more human and institutional in nature. A primary challenge is the fragmented accountability that exists across a complex network of contractors, transport providers, port authorities, and terminal operators. In many supply chains, no single entity has complete oversight or control over the entire journey from pit to port, making it exceedingly difficult to implement cohesive, end-to-end sustainability initiatives. Each partner in the chain typically operates with its own set of priorities and performance metrics, which are often focused on minimizing their individual costs rather than optimizing the environmental performance of the system as a whole. This diffusion of responsibility creates significant friction, hindering the data sharing, coordination, and shared investment necessary to drive meaningful, systemic change toward a more sustainable and efficient logistics network.

Compounding this fragmentation are legacy habits deeply ingrained in the industry’s culture, particularly the tendency to prioritize the lowest upfront cost over the total lifecycle impact of an investment. Decisions about vehicle procurement, route selection, and contractor choice have historically been driven by immediate budgetary considerations, with long-term environmental costs left unquantified and unaddressed. Furthermore, existing infrastructure bottlenecks often limit the viability of greener alternatives, regardless of a company’s intent. A mining operation may be eager to shift from road to rail, but if the local rail capacity is insufficient or unreliable, the transition is simply not feasible. Finally, uncertainty in policy enforcement creates a climate of hesitancy, discouraging the long-term, capital-intensive investments required for decarbonization. Overcoming these deep-seated challenges requires more than just technological innovation; it demands a concerted effort toward greater coordination, the establishment of shared standards, and stronger collaboration between operators and authorities.

5. The Cultural Bedrock of Modern Logistics

Ultimately, the most profound change that reshaped the industry was cultural. The concepts of sustainability, environmental impact, and carbon footprint transitioned from being abstract values in a corporate report to becoming fundamental operating conditions. In much the same way that safety standards had transformed mining practices decades prior, a deep-seated carbon awareness began to inform and shape daily operational decisions, from route planning and fleet selection to supplier and contractor choice. This evolution required a new type of leadership, one that was comfortable navigating complex trade-offs rather than seeking simple absolutes. It also demanded a great deal of patience and persistence from all stakeholders. The operational habits and mindsets that had been formed over generations did not change overnight, but they did begin to shift as economic incentives, regulatory accountability, and stakeholder expectations started to align in a powerful new direction. The companies that adapted to this new reality early on found themselves to be more resilient, more trusted by their partners and communities, and better positioned in a global market where supply chains were judged not just by what they delivered, but by how they delivered it. Those that waited discovered that relevance, once it was lost, was far more difficult to reclaim than it ever was to protect.