The financial world often buzzes with speculation about the Federal Reserve’s next move on interest rates, as if a single decision could universally satisfy the sprawling, diverse entity known as “the markets.” This notion, however, is far from straightforward, as the desires of market participants—ranging from savers to investors to corporate borrowers—are anything but uniform. The assumption that lowering rates is a panacea for economic woes or a guaranteed market pleaser overlooks the intricate web of competing interests and the fundamental question of whether the Fed can even dictate credit costs effectively. Digging into this topic reveals a landscape of disagreement, where market signals often clash with policy intentions, and historical patterns defy conventional wisdom. This exploration seeks to unpack the complexity of market dynamics and challenge the idea of a monolithic market stance on Fed actions.

Unpacking Market Dynamics and Fed Influence

The Myth of a Unified Market Voice

The concept of “the markets” as a singular entity with a clear preference for Federal Reserve policies is a persistent misconception that oversimplifies a deeply fragmented reality. Financial markets are not a monolith but a cacophony of voices—traders, institutional investors, retail savers, and corporations—all with divergent goals and risk appetites. Some might welcome lower interest rates for cheaper borrowing, while others, particularly those relying on fixed-income returns, dread the erosion of their yields. This inherent discord means that any Fed decision, whether to cut or raise rates, inevitably creates winners and losers. The idea that a single policy can satisfy such a varied group ignores the constant tug-of-war over economic uncertainties, where prices are set not by consensus but by the relentless interplay of supply and demand. Ultimately, the market’s response to Fed moves is less about unanimous desire and more about how individual actors interpret and adapt to new conditions, often in unpredictable ways.

Beyond the diversity of participants, the very notion of market sentiment is shaped by a continuous debate over information and expectations, further complicating any assumption of unity. Each player brings unique data points and forecasts to the table, whether it’s a hedge fund betting on inflation trends or a pension fund prioritizing stability. Historical evidence underscores this lack of agreement—stock indices have climbed during periods of rate increases, while at other times, cuts have coincided with declines. This variability suggests that markets price in far more than just Fed policy, including global events, corporate earnings, and consumer behavior. The Fed’s influence, while significant, often battles against these broader forces, making it questionable whether markets as a whole truly “want” any specific action. Instead, the market remains a battleground of competing narratives, where no single outcome can claim universal support, and policy impacts are filtered through a prism of individual priorities.

Credit Costs: Fed Power or Market Forces?

A critical aspect of the debate centers on whether the Federal Reserve can genuinely control the cost of credit, or if market forces ultimately hold sway, rendering policy interventions less effective than assumed. The Fed sets benchmark rates, but the actual price of credit—reflected in mortgage rates, corporate bonds, and personal loans—is determined by a complex dance of supply and demand. Even if rates are lowered, lenders may tighten standards or raise premiums if they perceive heightened risk, effectively offsetting the intended stimulus. This dynamic mirrors historical attempts at price controls in other sectors, where artificial pricing often leads to shortages or inefficiencies. In the credit market, similar distortions can occur, as artificially low rates might spur excessive borrowing or misallocate capital, creating bubbles rather than sustainable growth. Thus, the market’s true cost of credit often diverges from Fed targets, shaped by real-time economic conditions rather than central directives.

Moreover, credit itself is not a creation of central authority but a product of marketplace interactions, born from the exchange of goods, services, and labor over time. This perspective challenges the belief that the Fed can fully dictate credit flow or pricing, as historical examples of central planning reveal persistent mismatches between supply and demand. When rates are manipulated, unintended consequences often follow—savers lose purchasing power, while speculative investments may surge, skewing economic balance. The market’s role in setting credit terms becomes evident in these gaps, where participants adjust behavior based on perceived value and risk, not just policy signals. This raises doubts about the Fed’s ability to align its actions with a supposed market desire, as the underlying mechanisms of credit defy top-down control and reflect a broader, more organic economic reality that policymakers struggle to steer with precision.

Historical Patterns and Policy Implications

Savers, Investors, and Contradictory Outcomes

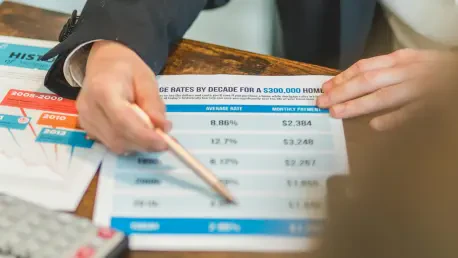

Delving into the impact of Federal Reserve rate decisions reveals a stark divide among market participants, particularly between savers and investors, whose interests often clash in response to policy shifts. Savers, a substantial segment, typically favor higher rates to secure better returns on deposits and fixed-income assets, as lower rates erode the compounding potential of their capital. This group might quietly resent rate cuts, which diminish their financial security, especially for retirees or risk-averse individuals. Conversely, investors in equities or real estate often celebrate cheaper borrowing costs, as they can fuel growth or asset price appreciation. Yet, historical data complicates this narrative—stock markets have sometimes thrived amid rate hikes, suggesting that broader economic strength or confidence can outweigh the drag of higher borrowing costs. This split highlights the impossibility of a one-size-fits-all policy, as the Fed’s moves inevitably favor some at the expense of others.

Further examination of past trends shows that market reactions to rate changes are far from predictable, undermining the assumption that lower rates are universally desired. During periods of significant rate increases, such as those totaling 525 basis points starting a few years ago, equity markets occasionally posted gains, driven by robust corporate performance or optimism about inflation control. In contrast, rate cuts in earlier downturns, like those around 2001 and 2007, coincided with market declines, as they often signaled deeper economic distress. These contradictory outcomes illustrate that markets interpret Fed actions through a wider lens of contextual factors, not just the direction of rates. For every participant hoping for relief through lower borrowing costs, another braces for diminished returns or heightened volatility, reinforcing the fragmented nature of market desires and the challenge of crafting policy that resonates across such a diverse landscape.

Centralized Control Versus Market Efficiency

Skepticism toward centralized control over economic variables like interest rates emerges as a recurring theme when evaluating the Federal Reserve’s role against the backdrop of market-driven outcomes. Proponents of market efficiency argue that decentralized decision-making, fueled by countless individual transactions, allocates resources more effectively than top-down mandates. The Fed’s attempts to steer credit costs or inflation often face resistance from natural market adjustments, as seen in persistent discrepancies between policy rates and actual lending terms. This tension echoes broader economic critiques of central planning, where government interventions historically led to inefficiencies or unintended side effects. The belief that markets, despite their noisy disagreements, better reflect true value through price discovery challenges the notion that the Fed can or should impose a uniform direction on economic activity.

Reflecting on this dynamic, it becomes apparent that the diversity of market participants inherently resists a singular policy prescription, favoring instead an organic balance shaped by competing forces. The Fed’s influence, while undeniable in setting short-term expectations, often wanes against long-term market signals like consumer confidence or global trade patterns. Examples abound of policy moves failing to produce expected results, as markets recalibrate based on real-world conditions rather than central bank forecasts. This reality suggests that entrusting inflation or credit control to a government-created entity may overlook the root causes of economic fluctuations, which often lie beyond bureaucratic reach. In retrospect, past debates over rate adjustments revealed a persistent gap between policy intent and market response, underscoring the limits of centralized authority in a system defined by constant, decentralized adaptation.

Reflecting on Past Lessons for Future Policy

Looking back, the intricate dance between the Federal Reserve and financial markets painted a picture of persistent tension, where assumptions about market desires often clashed with observable outcomes. Historical attempts to lower or raise rates frequently yielded mixed results, with some segments of the economy benefiting while others bore unintended burdens. The lack of consensus among market players—evident in the contrasting needs of savers versus borrowers—highlighted the challenge of aligning policy with a supposed collective will. As discussions unfolded over the years, it became clear that the Fed’s tools, though powerful, operated within a broader ecosystem of independent forces that shaped credit and growth in ways no single entity could fully predict or control. This realization framed much of the critique surrounding centralized interventions, as past policies often stumbled over the market’s inherent diversity.

Turning to actionable insights, future considerations for monetary policy might focus on embracing flexibility over rigid targets, allowing market signals to play a larger role in setting economic benchmarks. Policymakers could prioritize transparency in communicating intentions, helping participants adjust expectations without over-relying on rate adjustments as a cure-all. Additionally, fostering environments where savers and investors alike can find stability—perhaps through targeted fiscal measures rather than broad monetary shifts—could mitigate the divisive impact of rate changes. Encouraging dialogue between regulators and varied market stakeholders might also uncover more nuanced needs, moving beyond oversimplified narratives of what markets supposedly want. These steps, grounded in lessons from earlier policy cycles, offer a path toward balancing intervention with the organic, often unpredictable, rhythm of financial systems.